This is the first post in a three part series about latent profile analysis. Three posts you say?! Yes. This is the statistical method I used in my dissertation, so needless to say I have lots of thoughts about it. This first post will provide some theoretical background on mixture models more generally, and latent profile analysis (LPA) specifically. If you are curious one of the most accessible articles about finite mixture models out there is Kathryn Masyn’s (2013) chapter in The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods in psychology.

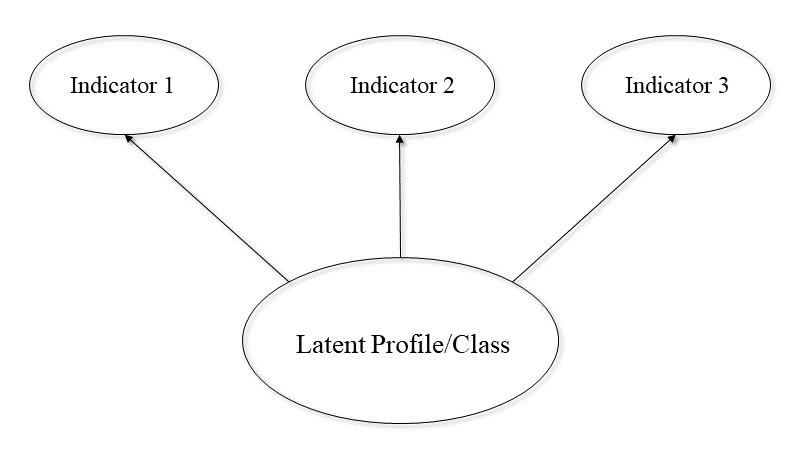

Finite mixture models are part of the structural equation modeling framework. If you are familiar with structural equation models at all you know that path diagrams play a major role in describing analyses and associations between variables. Fortunately, the basic path diagram for latent profile/class analysis is quite simple. Unfortunately, its simplicity belies the actual complexity of the model.

Mixture models assume there is unobserved heterogeneity in a sample of observations. Meaning, an overall sample is actually a mixture of several subpopulations, each with their own distinct characteristics among a certain set of indicators. These subpopulations are modeled as latent variables and given the name latent classes (LCA) in the case of categorical indicators, or latent profiles (LPA) in the case of continuous indicators. The latent classes or profiles are defined by at least three, and generally no more than seven or eight, indicator variables. For example, we could create profiles of professional cyclists using indicators such as sprint speed, climbing ability, and endurance.

There are three ways to model Indicator variables. They can be latent variables, factor scores, or observed variables. Although modeling indicator variables as latent sounds tempting initially, adding the complexity of latent indicators to an already complicated model oftentimes proves to be too much, and it is common to run into difficulties getting LPA/LCA models to replicate or converge. Modeling indicators as observed variables eliminates this issue; however, using a simple mean of items in a composite variable do not always accurately represent the latent variable they were designed to indicate. Factor scores present an opportune middle ground. Modeling LPA indicators as factor scores, as opposed to a composite mean, retains some of the benefits of modeling indicators as latent variables, but without the complexity that results in uninterpretable solutions.

Running LPA/LCA analyses take a substantial amount of time and computing power. One reason is the necessity of comparing model fit across multiple model types. The profile identification process in LPA involves examining several different models with various assumptions about the mean, variances, and covariances of the indicator variables used to construct the profiles. Additionally, for each model type, models with a varying number of profiles may be specified (e.g. 2 – 7 profiles). More details about this process are in Part 2 of the series, but a quick introduction to six common model types used in LPA/LCA are below:

- Varying means, equal variances, and covariances fixed to 0

- Varying means, equal variances, and equal covariances

- Varying means, varying variances, and covariances fixed to 0

- Varying means, varying variances, and equal covariances

- Varying means, equal variances, and varying covariances

- Varying means, varying variances, and varying covariances

Importantly, the number and nature of the profiles or classes present in the sample, along with each observation’s membership in these classes or profiles, is unknown prior to analysis. The goal of mixture modeling is to identify the sub-populations present in the sample, and assign observations to those sub-populations using mixture probabilities. Continuing our example, if we had a sample of 1,000 cyclists we may find that some cyclists excel in all three of our indicator variables, while others might be good climbers and have good endurance, but have poor sprinting ability. Of course those are only two examples of profiles we might find. There are many other possibilities. The point is that the indicators used to create profiles can vary in many unique ways, leading to distinct profiles.

Mixture models share an underlying goal with traditional clustering approaches (grouping observations based on key indicators); however, a key benefit of using mixture modeling, in addition to likelihood estimation-based fit indices, is that probabilities of profile membership are utilized, unlike cluster analysis which hard code observations into profiles. This means that the uncertainty of profile membership is accounted for when calculating profile indicator parameters (i.e. means, variances, covariances)

After profiles are identified the next question might be: What do we do with them? Well, for one, latent profiles are a unique way to describe the relationships between a set of variables. Mixture models are commonly classified as a person-oriented approach, in contrast to variable-oriented approaches. Variable oriented approaches include many familiar statistical techniques including regression, structural equation models, multilevel models, etc. These techniques describe relationships between individual variables, controlling for effects of other variables. Person-oriented approaches allow researchers examine how multiple theoretically related variables vary simultaneously.

Person-oriented analyses are particularly useful when the indicators vary substantially within profiles and when these profiles are either predicted by, or predict, variables of interest. In our cyclist example once we have identified a set of profiles we might then use them to predict times in certain tour de France stages, or predict membership in these profiles with specific training regimens. It is easy to see how helpful knowing the association between a certain type of training and profiles with high climbing ability or quick sprint speeds would be.

It is important to keep in mind that latent profile analysis is a very exploratory statistical methods that assumes a priori the existence of subpopulations present in a sample, even if no subpopulations exist. Also, because of the exploratory nature of LPA it is important to replicate results in multiple independent samples prior to making any strong inferences about the nature of class/profiles present in a population.

In Part 2 of this series we will construct a set of profiles using the tidyLPA R package!

References

Masyn, K. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 551-611). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199934898.013.0025

One thought on “Finite Mixture Modeling – Latent Profile Analysis, Part 1”